By Zeynep Sentek, Jelena Prtorić, Sarah Pilz

15 May 2024

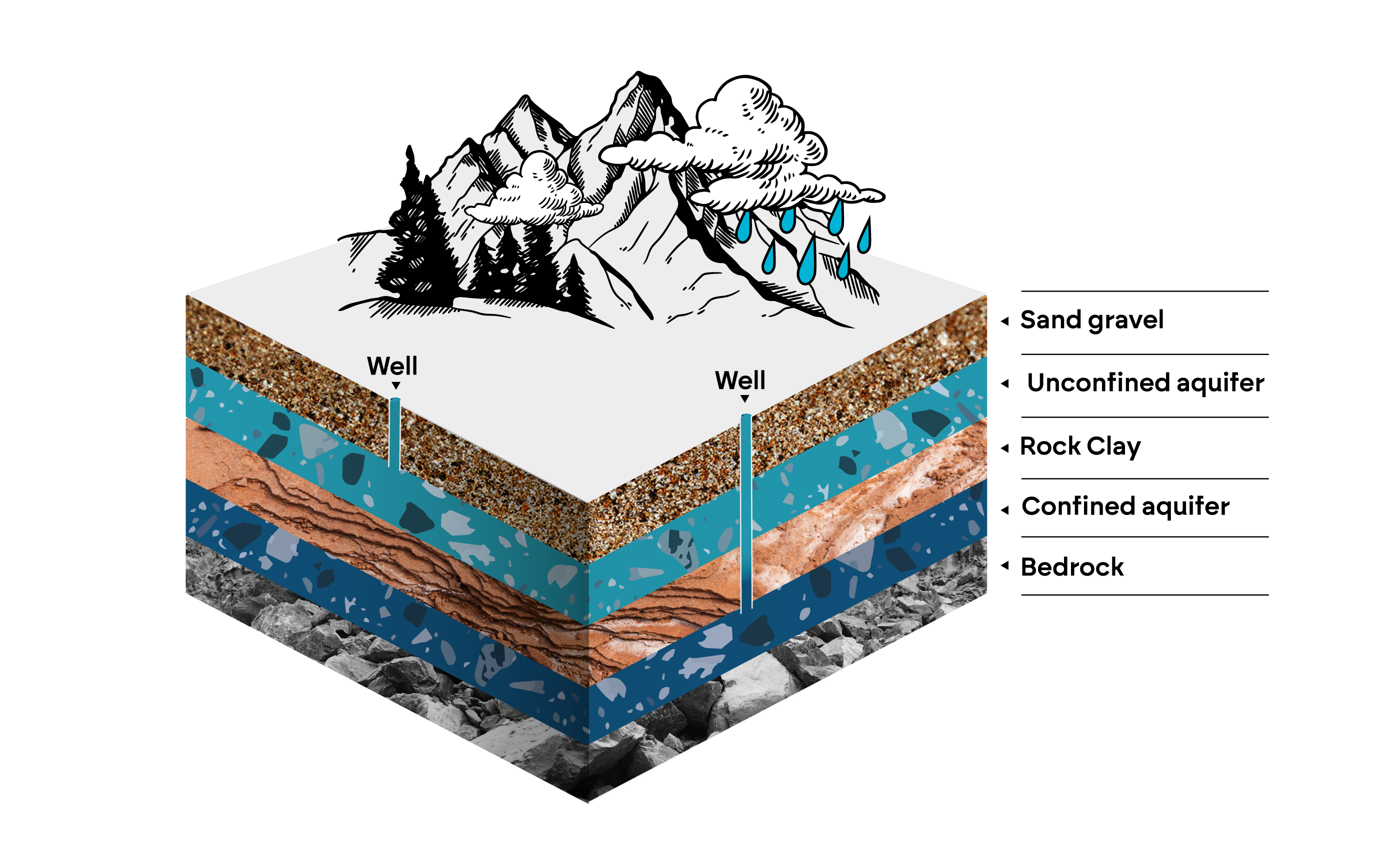

Europe has long been proud of its clean water: accessible, abundant, and drinkable. Most of what we drink, irrigate our crops with, and use in our industries, comes from deep underground, from within vast labyrinths of aquifers. This precious groundwater sustains an entire continent and has helped turn Europe into one of the most sanitary and prosperous regions in the world.

About a hundred years ago, nations began to tap ever deeper into the earth to extract water, confident that this infinite resource would forever be replenished by rainfall. It took nearly a century, but our understanding has shifted drastically. Scientists have warned in recent years that this delicate system is in crisis. And that climate change and industrial overexploitation have resulted in a dramatic decline in the quality and quantity of underground freshwater in Europe.

The Under the Surface project, coordinated by Arena for Journalism in Europe and initiated by Datadista, delved into official data from European countries to reveal, for the first time, the extent of the danger we face.

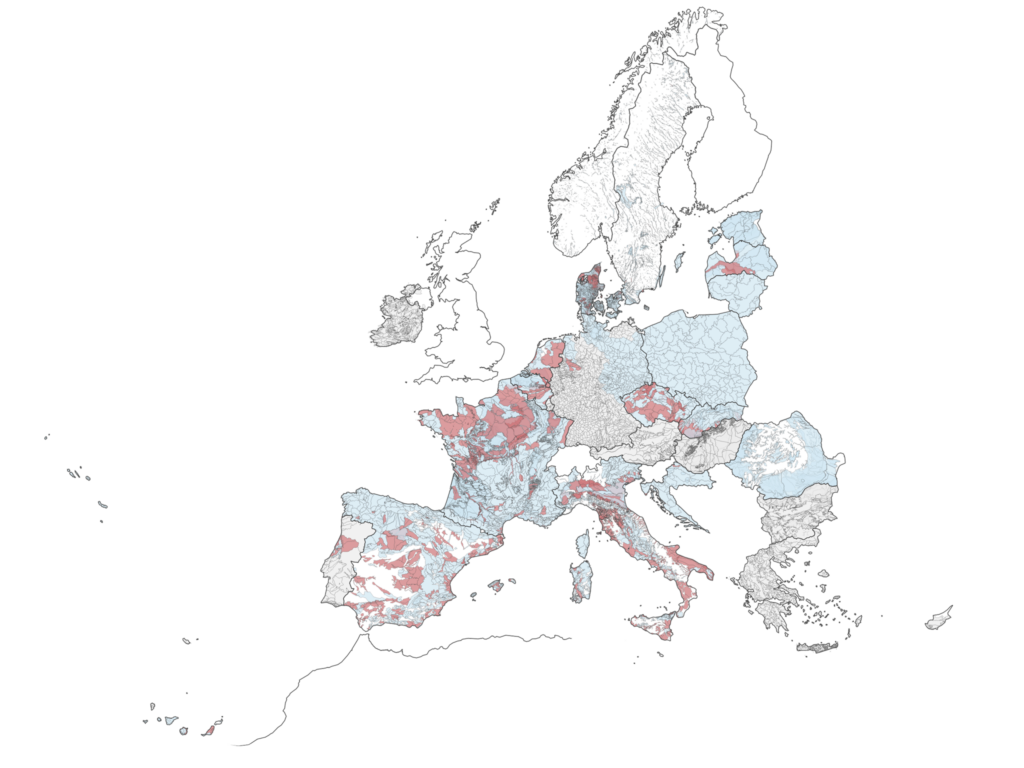

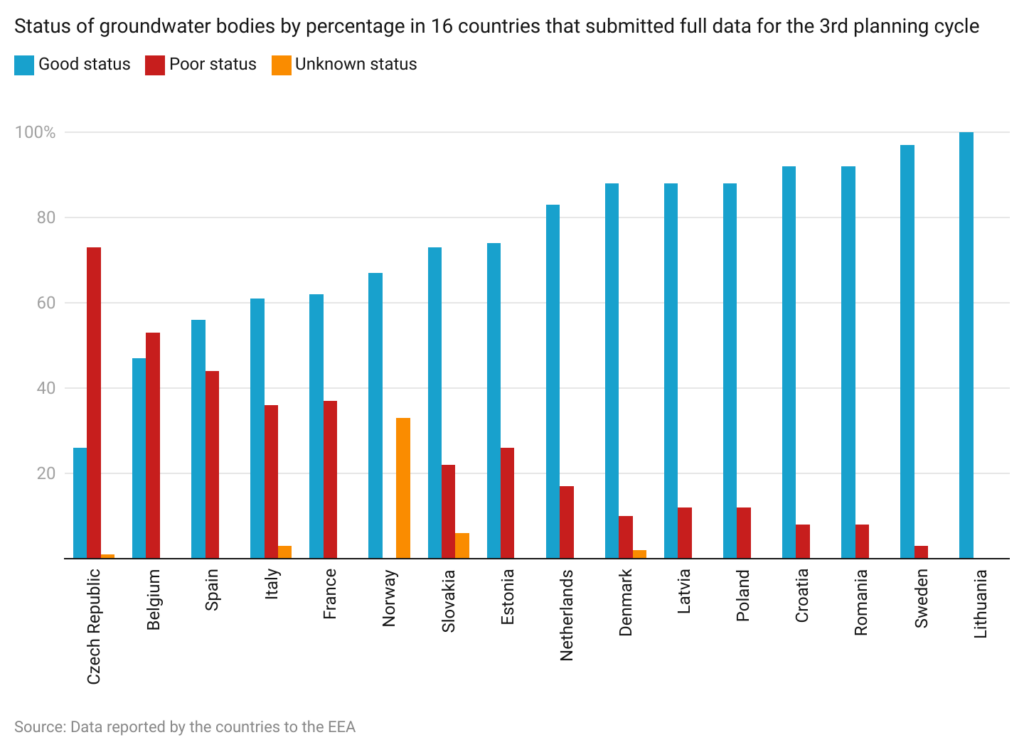

Altogether, 14 journalists from seven countries analysed the most up-to-date EU figures and created an interactive map of Europe’s aquifers. The conclusion is that our water is disappearing and what remains is facing near-irreversible pollution. Over 15% of the aquifers mapped are in poor condition — dangerously overexploited, contaminated or both. This figure represents 26% of the aquifers by surface area. And the worst affected are important crop-producing countries, like Spain, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

But the picture is incomplete. The EU requires all member states and Iceland and Norway to give data on the state of their aquifers. Out of these 29 countries, 16 submitted full, publicly accessible data, with Germany’s and Portugal’s only partially accessible. Eleven countries are not included in the map at all: ten provided no information whatsoever to the EU, and one, Austria, opted to keep hidden key parts of their data that prevent it from being mapped. Scientific experts, shown the findings of the Under the Surface project, warned that without the full data, we cannot know the true extent of the damage to the continent’s groundwater.

Despite the perilous state of affairs in key areas, the EU not only routinely fails to force countries to abide by the minimal requirements of current legislation, it is watering down its commitments, often under pressure from agricultural and chemical industry lobbying.

Belgian fruit growers, Spanish villagers, Italian rice farmers, and Greek islanders – they all share a common hardship: each year brings drought and an over-reliance on polluted water that impacts their daily lives and businesses. Over the past months, as Europe prepares for another record-breaking summer, we talked to these communities, and a host of scientists, experts, and policymakers, to understand the consequences we all face in a Europe that is drying out.

Europe is running out of water

“Water has become our biggest concern,” Bart Trybou said. “Since the dry summer of 2017, it has been an anxious wait every year. The extreme weather is eating away at our yields.” Bart and his wife Evelien Vanlerberghe run a large agricultural company in West Flanders, Belgium, that grows cauliflowers, zucchini, and spinach for the frozen vegetable industry.

Belgium is the world’s largest exporter of frozen vegetables. Farmers like Bart and Evelien are desperate to keep their businesses afloat. From their office in Houthulst, Bart explained, with a sense of solemnness, their dilemma. “In winter and early spring, it is too wet for our crops. Then things change and our fields are too dry. We can only save our crops by irrigating. If you don’t irrigate, everything is lost. But if you do, your profits will evaporate. Water is difficult to find and expensive,” he said. “It is no longer sustainable this way. More and more growers are giving up.”

Our research shows that groundwater in the EU is under such significant pressure from excessive irrigation, industrial overexploitation, and a cocktail of pollutants, that the resulting water scarcity is serious enough to upend livelihoods and even entire sectors.

“Europe has a major water problem,” said Hans Bruyninckx, professor of environmental governance at the University of Antwerp. “In some areas, it is becoming extremely urgent. Scientists have been predicting this for many years. Now we are at that point. There are places that have reached a point of no return.”

Our interactive map below shows the quality and quantity of groundwater across 18 countries — 17 in the EU, and Norway. It covers nitrates and a limited range of pesticides and metals. Problematic substances like PFAS – known as “forever chemicals” – and pharmaceuticals are not included because the EU does not require testing.

The map reveals that 15% of the water bodies included in the map are in “poor condition” which represents 26% of aquifers by area coverage. Significant depletion or pollution in larger aquifers is likely to have a broader impact, as these often serve a wider region and larger population. In the Czech Republic and Belgium, the number of aquifers designated as “poor” outnumber the healthy ones. But they are closely followed by Spain, France and Italy.

INTERACTIVE MAP: Know the status of the European Union groundwater

| IMPACT | DESCRIPTION OF THE RISK |

|---|---|

| L | Groundwater level decrease (aquifer depth, water volume) due to extractions. |

| N | Nutrient pollution, mainly from fertilizers and animal waste, above the legal limit (50 mg/l) or close to the limit with an upward trend. |

| C | Chemical pollution other than nutrients (mainly pesticides but also metals, hydrocarbons, etc.) above the legal limit or close and with an upward trend. |

| E | Impact on terrestrial ecosystems dependent on groundwater. |

| M | Microbiological contamination. |

| O | Organic contamination. |

| IMPACT | DESCRIPTION OF THE RISK |

|---|---|

| Q | Decrease in surface water quality associated with chemical or quantitative impact. |

| I | Alterations in the direction of water flow due to saline intrusion. |

| S | Saline intrusion or contamination. |

| T | Other types of significant impact. |

| N | No significant impact. |

| A | Acidification of water bodies. |

| U | Unknown impact type. |

| H | Altered habitats due to hydrological changes. |

| Y | Altered habitats due to morphological changes (includes connectivity). |

Details of our data and mapping methodology, and further explanation on how to interpret the map, can be found here.

“We have lived well beyond our means for decades on the assumption that water is infinite,” said Henk Ovink, director of the Global Commission on the Economics of Water, an expert group facilitated by the OECD. Ovink is one of the world’s premier advocates for sustainable water practices, once nicknamed the “water guy” by President Barack Obama. “But our actions are changing the course and availability of freshwater. We can no longer count on water being there for us.”

Our map is based on information that each member state delivers to the EU Commission. The “good status” aquifers are shown in blue; those in red are in “poor status”. Each country is free to design its methodology, although the EU provides guidelines on data collection. The lack of uniformity can occasionally lead to inconsistency or misreporting. Some countries’ maps often appear in better condition than in reality. “Croatia has major water problems but is blue on the map. That is not realistic,” Hans Bruyninckx said. “Wallonia and the Netherlands hardly have any groundwater problems? Impossible.”

Elisabeth Lictevout, a hydrogeologist and director of the International Groundwater Resources Assessment Centre (IGRAC), suggested that while “countries may have the tendency to report [their groundwater status] as better than they are,” they will never report it as worse. “This map is the best-case scenario,” she said.

Ovink, Bruyninckx and Lictevout argue that the crisis is far bigger than the map suggests. “It seems that a lot of data isn’t reported,” Ovink said. “Which means that a lot of stakeholders and countries are absolutely not taking this problem seriously enough. They are avoiding the science and the data telling us we are operating in the danger zone.”

“When water disappears, everything ends”

European customers enjoy a diversity of cheap produce in their supermarkets all year round. Traditional seasonal crops are a thing of the past. There are peaches in February and squash in August. European olive oil, once a largely local, rain-fed product, is now a global obsession, used in everything from salads to soap – a multi-billion industry that exports to the entire world.

The EU has funded this mass production through lavish subsidies from its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). One-third of the EU’s budget – 54 billion euros annually – goes to CAP. This generous system has propelled the EU into an agricultural superpower, and countries like Spain to the big leagues of global food producers and exporters.

But it all has come at a cost.

Spain is one of the countries in Europe most impacted by degraded aquifers. Almost half of its groundwater bodies are in poor condition in terms of quality and quantity. Around 27% are overexploited, with the majority in the south and east, traditional farming regions now with vast intensive agricultural production.

Spain offers a cautionary tale to the rest of the continent: a success story built on the pillaging of scarce resources now skirting perilously close to a collapse. The country produces millions of tonnes of fruit, vegetables, and livestock each year, much of it for the continent. The consequences of significant disruption would be felt everywhere. “We put everything at risk, starting with food, energy, health and nature – if we do not restore the global water cycle,” said Henk Ovink. “There is no alternative to water. When that disappears, everything ends.”

The climate crisis is fuel on the fire. The lack of rainfall in dry countries like Spain and Italy results in communities and farmers relying more on groundwater. Aquifers, already under pressure, cannot replenish fast enough to keep up with demand. One study estimates that around 52 million people in the EU and UK are at risk of water scarcity, with 3.3 million facing “severe scarcity.”

What about the famously grey and rainy parts of Europe? The picture emerging is equally disconcerting. Aquifers in countries like Belgium, France, and Germany are experiencing alarmingly low levels.

Our research shows that in Belgium water bodies are under serious pressure, with 75% of deep aquifers considered overexploited and the majority of its shallow groundwater contaminated by excessive levels of nitrates, caused by fertilisers.

Wet winters and summer rains provide only the illusion of plentiful water. “Due to climate change we have more extreme conditions: longer periods of drought and other periods with more rain,” explained Patrick Willems, professor of hydrology at KU Leuven in Belgium. Rain from heavy downpours saturates topsoil and washes off the ground too quickly to be absorbed by the earth and into aquifers. “Rainfall only affects the levels in shallow water bodies,” Willems added. “The deep groundwater is sealed by almost impermeable layers. It takes decades or even centuries to recover the deep groundwater.”

“We’ve turned our groundwater into a garbage can”

Empty aquifers are not the sole concern. Many European countries must also grapple with the effects of decades of pollution that sullies what water remains underground.

Climate activists, scientists and public health professionals have routinely criticised the EU for providing substantial CAP funds to farmers and agricultural companies that profit from super-intensive monocultures, which strip out the nutrients from the soil until nothing grows without chemical pesticides and fertilisers. These substances seep through the earth and contaminate underground water, rendering it unsafe for human consumption and impacting biodiversity.

Groundwater pollution linked to agriculture’s overuse of nitrates in fertilisers, manure and pesticides is widespread in Europe, but particularly pronounced in agricultural hubs of Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Italy, and France. And the problem is cumulative. As groundwater levels fall, the pollution becomes more concentrated.

In Spain, we visited towns where aquifers that had sustained communities for centuries have dried up or become contaminated by nitrates and other dangerous elements. One of these is arsenic, a poisonous heavy metal naturally present in underground rock formations, which gets released into the waters of deep aquifers as they become overexploited. For years, the 350 residents of Lastras de Cuellar, a small village in central Spain, were forced to depend on daily deliveries of bottled water after the public supply became undrinkable due to nitrate and arsenic contamination.

“No one is aware of what it’s like to live without potable water. It’s not just about drinking it. It means you cannot eat an apple washed under the tap. You cannot cook with it. You cannot brush your teeth,” Mercedes Rodriguez told us. Inhabitants tried for years, she said, to attract the attention of the authorities.

“We called not only the provincial council but also the regional government and all the political parties in Segovia,” she said. “Truth be told, they all came. We offered them a glass of the same water they forced us to drink, but nobody wanted to try it. If Lastras could drink water from the tap, we didn’t understand why they wouldn’t drink it. None had the courage to take a sip.”

In protest, they hung the plastic bottles from the water deliveries on their balconies and around the town. They dumped more in the town square and displayed banners demanding “Drinkable water now!”

Two years ago, they won a victory of sorts. The regional administration installed new pipes and connected them to a neighbouring water source, at a cost of €1.2 million, a hefty price tag for a town of 350. Their own water will likely never recover.

France’s water showed widespread chemical pollution from pesticides, the primary source of aquifer contamination. Some of these are from decades ago. The carcinogenic and toxic molecules of Atrazine, banned in 2004, can still be found in the aquifers.

“We’ve really turned a blind eye to the fact that water collects all these [poisonous] molecules, which circulate very slowly,” says Florence Habets, hydroclimatologist at the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), in France. After we showed her our findings, she said, “We’ve turned our groundwater into a garbage can, and that’s going to have an impact over a very long time.” France has been forced to shut down 1300 wells over the past 30 years because of irreversible levels of chemicals in their water.

The examples in Spain and France are extreme and challenge a myth central to ‘European civilisation’: tap water in EU countries is plentiful and drinkable and will forever remain so.

This essential, life-sustaining liquid which flows so freely into our homes already requires extensive – and expensive – water treatment to filter harmful substances. The cost of this journey from ground to glass is borne by the public –or, increasingly, customers of private water firms. The higher the number of pollutants, the higher the cost of making water drinkable.

The principle of ‘polluter pays’ is enshrined in the EU Treaty. In practice, it exists only on paper. The EU’s legislative mechanism to sanction countries –the so-called infringement proceedings – is long, slow, and a last resort. The industrial and agricultural polluters of groundwater are rarely hit with a bill. On a national level, countries that fail in their duty to implement EU regulations or directives are usually just “called on” to fix the situation.

Experts argue that technology can help. Desalination and purification plants successfully clean water of salt or pollutants but have significant downsides: financially and environmentally. These processes are energy-intensive and need a lot of electricity, which means fossil fuels. They also create byproducts that require proper disposal.

“Chemical pollution is also an inequality issue,” says Hans Peter Arp, professor of environmental chemistry at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. “Some countries don’t have the same capacity to monitor the water, let alone finance expensive technical solutions and infrastructure. The Netherlands might be able to implement reverse osmosis [water purification] and finance it. But for lower-income countries in the EU, this might be impossible.”

No measurement, no problem

EU countries must submit data on the quality and quantity of their groundwater every six years. The most recent data is collected from 2018 until 2021. This monitoring and reporting is an obligation under an ambitious EU legislation known as the Water Framework Directive, which strives to ensure the bloc’s groundwaters achieve “good status” by 2027.

When we processed the map, it showed that over half of the bloc will fail to achieve “good status.” Countries like Germany and Spain have already admitted this publicly.

“Some governments are working on this issue, but it’s not happening fast enough. We will never meet the 2027 deadline,” says Hans Bruyninckx. Countries like Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Greece, Iceland, Malta, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg and Slovenia are 2.5 years late in submitting the required information on the status of their groundwater.

In some countries, problems are more structural. In Greece, there are no groundwater measurements taken in 2016-2017 and since last October. The Greek National Water Monitoring Network is funded exclusively by the EU; when the funds are unavailable, authorities do not carry out the necessary measurements.

Reversal is possible, if we want it

The experts we spoke to unanimously believe that tackling groundwater pollution and depletion requires a systematic approach. “It is possible to reverse this,” said Elisabeth Lictevout. “But nobody wants to speak about over-extraction or consumption. We need to take strong action now on water management. We need to extract less. If we continue the way we are, there is no way to revert.”

In late 2023, the EU Commission announced a Water Resilience Initiative to push for water sustainability and access across the bloc, as part of the “European Green Deal.” The proposal, to “ensure access to water for citizens, nature and the economy, while also tackling catastrophic flooding and water shortages,” garnered support from a range of stakeholders – not only the usual environmental NGOs but the industry too. Barely five months later, the commission backtracked and placed the initiative on indefinite hold.

“The initiative isn’t legally binding, but it would recognise the need to tackle water issues and put them on the political agenda,” said Sara Johansson, senior policy officer at the Brussels-based European Environmental Bureau. “It could have been potentially perceived as a threat to agro-industry. Everything related to agriculture at the moment is very sensitive.”

Lately, the EU has been softening its climate approach, capitulating to political pressure from far-right parties and farming and agrochemical lobbies. “The dumbest thing we can do now is to pull back, as Europe is doing by weakening environmental legislation,” said Ovink. “That setback will make things much worse”.

Bruyninckx agreed. “We are going over tipping points. We are going deep into the red,” he said. “It is shocking that politicians are not taking this seriously. They seem to think, or falsely hope, that it will all be fine. Scientific evidence is now almost screaming: it will not be OK.”

Reporting team: Zeynep Sentek, Jelena Prtorić, Sarah Pilz, Ine Renson, Maxie Eckert, Ana Tudela, Antonio Delgado, Raphaëlle Aubert, Myrto Boutsi, and Léa Sanchez.

Arena for Journalism in Europe coordinated this project and Journalismfund Europe supported the Greek, Spanish and Italian reporting and the map work. For full credits and how the project came about and how we did it, you can see the About page.